Defending the Defenders

By Kevin Dixon, Vice President of Programs and Operations at IJM Canada

There’s a noble sentiment that “it is amazing what you can accomplish if you do not care who gets the credit.” I think Canadian lawyer and human rights advocate John Humphrey would have agreed. Humphrey, a professor at McGill Law School who went on to become the first director of the United Nations’ Division of Human Rights, authored the first draft of the U.N.’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights and guided it to completion in 1948. Yet, it was the French jurist René Cassin who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1968 for his role in it. With noble sentiments in mind, John Humphrey appears to have lived happily by the principle that results are more important than recognition.

People like John Humphrey and René Cassin had their own personal stories of how they became human rights advocates. Humphrey, for instance, had a difficult childhood: his parents both died of cancer and then he lost an arm while playing with fire. He was teased for his disability by other boys at boarding school in New Brunswick and Humphrey later claimed this was influential in building his character. René Cassin, born in Bayonne, left the practice of law in 1914 when he was drafted into the French infantry where he was severely injured by German shrapnel in 1916. Later that year Cassin accepted a professorship at the University of Aix-en-Provence and, despite chronic pain that plagued him for the rest of his life, became widely regarded for his scholarly contributions to the field of international law.

Humphrey would have concurred with Cassin’s observation that “men are not always good,” but that “responses can be constructive if States transform the conditions that breed ill will into those that recognize the dignity” of human beings. Personal hardship laid a foundation for both men’s work in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, shaped their outlook on life, and influenced their determination to improve the world’s condition.

Neither man lived long enough to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the United Nations in 1998, and consequently weren’t there to celebrate that year’s adoption of the U.N.’s Declaration on Human Rights Defenders. In their own way, however, long before the role had been articulated and adopted by the United Nations, John Humphrey and René Cassin fit – perhaps influenced – the recognized definition of a Human Rights Defender (HRD). HRDs are individuals, groups and associations that contribute to the effective elimination of all violations of human rights and fundamental freedoms of peoples and individuals. You and I are human rights defenders to the extent that we support victims of human rights violations, support actions that lead to accountability, and encourage education and training about human rights work. It doesn’t matter if we get credit for what we do or not.

International Justice Mission’s dedicated men and women, who work tirelessly to defend the rights of the world’s most vulnerable, can take solace in the fact that their efforts have been formally acknowledged by the United Nations for these past twenty years. The same goes for countless other human rights defenders working with other organizations or alone. Now, in 2018, not only are human rights defenders acknowledged, but also protected to the extent that the UN is able to stand between them and the recrimination they may experience for defending the rights of others.

This summer, during the 20th anniversary year of the Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, I had the privilege to hear an address by Michel Forst – the UN’s Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders – to more than 100 human rights defenders assembled at the René Cassin Foundation’s International Institute of Human Rights in Strasbourg, France. Mr. Forst said:

“In societies undergoing political upheaval or transition… human rights defenders are among the first to take advantage of small democratic openings. They are among the first to organize and participate in public demonstrations, to take advantage of the smallest opportunities for freedom of speech.

Defenders keep the fundamentals alive – including truth and justice for victims of human rights violations – principles that may be vulnerable to the political pragmatism that often prevails during periods of transition.

“Many become defenders by necessity, or by resistance to fatalism, or because the only alternative is despair. Many do not see themselves as defenders. This is especially the case in rural communities; sometimes they reject this identity: too honorific or heavy to wear. I have asked, ‘Do indigenous leaders consider themselves defenders?’ Some answer me with a lot of humility, ‘Me? I only defend my life and that of my family. Our land is our culture. And without our culture, we lose our identity. Without that, what would become of us?’”

I recall an occasion in El Salvador several years ago when I met a Salvadoran lawyer representing a community group near the Honduras border that opposed the development of a copper mine by a Canadian mining company. The proposed mine had the potential to contaminate the region’s drinking water supply. The lawyer told me about anonymous threats he and his family had received. Our conversation occurred in the context of a broader discussion about the death of Marcelo Rivera, a local teacher who had advocated for his rural community’s right to clean water, and whose body was found dumped in a well. Both men – one alive, the other dead – were human rights defenders.

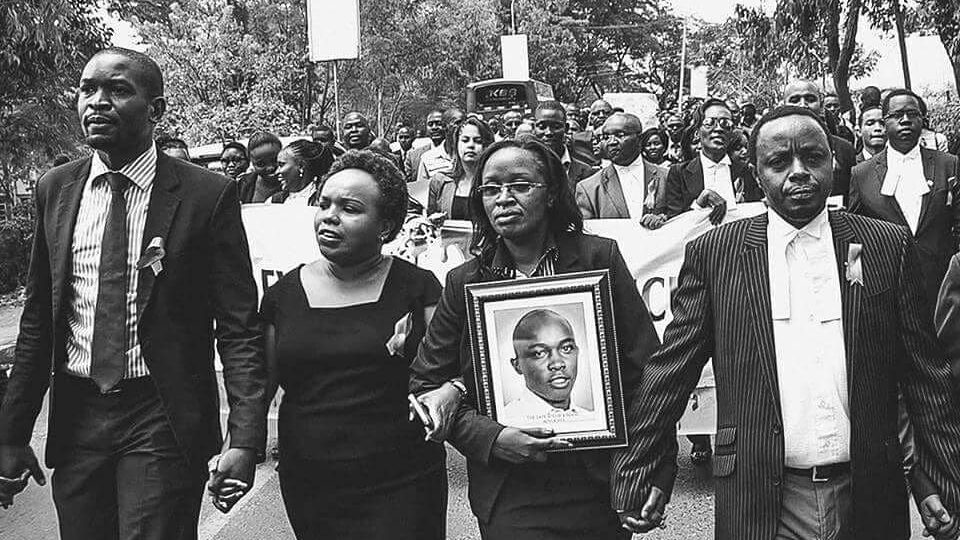

IJM’s most horrific example of what can happen to human rights defenders is Willie Kimani of Kenya. In 2016, Willie – an IJM lawyer – was abducted and killed for his role in representing a client, Josephat Mwenda, who had filed corruption charges against a Nairobi police officer. The officer had charged Josephat with crimes of possessing drugs, gambling in public and resisting arrest. These charges appear to have been in retaliation for Josephat’s formal allegation that the same police officer had shot and injured him. The case is still before the courts in Nairobi, due to resume this October. Four police officers are on trial Four police officers are on trial for the brutal murder of Willie, Josephat, and their taxi driver Joseph Muiruri.

Thank God for heroic men and women who commit – and sometimes sacrifice – their lives for the cause of justice, and in defence of basic human rights and freedoms. There exist rare examples like John Humphrey, René Cassin, and Willie Kimani, but countless everyday heroes like you and me can stand alongside and defend the defenders. The Freedom Commons is a good place to learn more about how to advocate for IJM’s human rights defenders and the vulnerable children, women and men they seek to defend. Also, the website of the United Nations’ Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights provides a wealth of information about the UN’s human rights treaties and how the Commissioner’s Office does its work to protect human rights and HRDs.

By the way, the axiom, “It is amazing what you can accomplish if you do not care who gets the credit” is generally attributed to former U.S. President Harry S. Truman. In fact, credit should probably go to a 19th century English Jesuit named Father Strickland who said to the Scottish politician Sir Mountstuart E. Grant Duff, “I have observed, throughout life, that a man may do an immense deal of good, if he does not care who gets the credit for it.” Sir Grant Duff was so impressed by the wisdom of the saying that he recorded the quote in his diary on September 21, 1863.

Sometimes, credit can go where it deserves. Canadians who remember John Humphrey honour one of our own defenders of human rights.